Haute History: Valentina

She was a known liar, so it’s hard to know the exact true story of American couture designer Valentina’s life.

It was always only Valentina; she was purposefully mononymous, never known by her actual name, Valentina Nicholaevna Sanina Schlee. Born somewhere around 1899, possibly even as late as 1904, near Kiev, in what was then Russia. From an early age, Valentina wanted to become an actress. She had some sort of formal theatre training and did spend time performing on stage.

We know that she fled the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, meeting the man that became her husband, George Schlee, theatre producer/financier, Millionaire, at a railroad station while trying to escape the country.

The story is that he protected the seventeen year old, who was traveling alone and supposedly had family jewels with her. Heirlooms they may have traded for fake Greek passports, which the couple then used to get into western Europe. They spent several years bouncing around the continent before emmigrating to the United States in 1923.

Valentina was a lot of things, objectively beautiful, charming, and purposefully misleading. She let people assume she was a titled aristocrat who had been forced from her home country during the revolution, though that seems to be completely fake. She told stories about her childhood theatrical training, that she had been a professional ballerina and actress while traveling with her husband across Europe; both stories that may have been partially true but were definitely embellished.

U.S Immigration records do have the Schlees listed as affiliates of a dance troupe they were traveling with, which is one of very few independent sources that confirms something Valentina said about her life before America. There are almost no records about her early life.

In America, Valentina still wanted to be an actress, but regardless of any talent she might have had, her English (or maybe her accent?) was too terrible for her to get roles. Once settled with her husband in New York City, she tried and failed twice in the mid-1920s to start a fashion business, but Schlee was successful in the stock market, building on his existing family fortune. He began to again produce and finance theatre productions, which gave his wife increasing exposure as a designer. Valentina attended his events, and was seen and recognized by elite circles of New York society. A beautiful woman who always dressed in her own impeccable designs, people took notice and began to ask her to make them clothing.

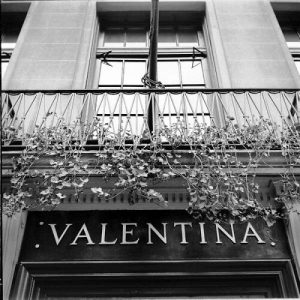

‘Valentina’s Gowns’ opened in 1928; a venture backed by Wall Street financier and attorney, Eustace Seligman, represented by famed publicist Eleanor Lambert. It was an overnight success. Schlee managed the business, the brand’s workrooms staffed by members of his own extended family.

In the early 1930s, she began to design costumes for theatre and opera, by the second half of the 1930s she had hand picked an A-list, clientele. Actresses like Lillian Gish, Jennifer Jones, and Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo and Gloria Swanson, as well as wealthy society ladies from families like the Vanderbilts and Whitneys.

By the 1940s she was designing costumes for film. Perhaps the best proof that she really did have professional theatre training would be her seemingly innate ability to define a character on stage with costume. Theatre critic Brooks Atkinson once said (of her costume design work) that “Valentina has designed clothes [costumes] that act before a line is ever spoken.”

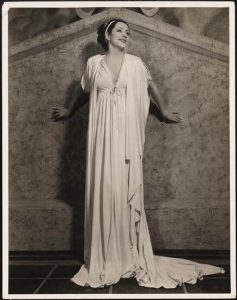

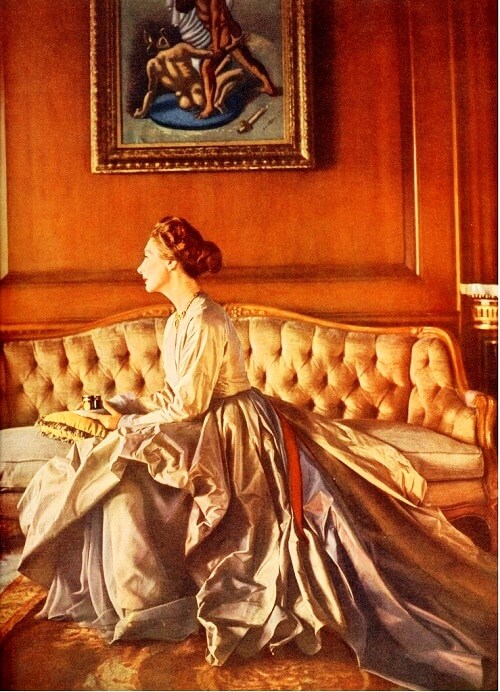

Like her costume work (one of her more famous designs, the white crepe gown Katherine Hepburn famously wore in the 1939 stage production of The Philadelphia Story, pictured above) Valentina’s apparel designs were deceptively simple. In an era known for feminine details and elaborate ornamentation, her work was modern, monochromatic, and sometimes austere. The evening gowns, cocktail dresses and daywear she created were all made on commission, in a manner reminiscent of French haute couture. Every piece was made to measure, finished by hand, and any client the designer deigned to accept was subject to multiple, fastidious (excessive?) fittings.

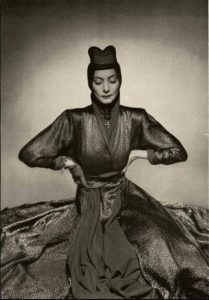

As a designer, her desire was to create timeless looks, clothing not defined by an era. She famously said that women should dress to “…fit the century. Forget about the year!” Her apparel was sleekly draped, often with floor-skimming skirts with dramatic necklines and backs. Valentina’s clothing was frequently compared with that of contemporary haute couturiers Madame Grès and Madeleine Vionnet. Known for her absolute obsession with detail, she had incredibly high standards for her designs, for the work that would carry her name.

Valentina would not compromise, ever. She had decisive opinions, did not care what anyone thought; argue with her too long and she would drop you as a customer. She refused to have more than two hundred clients at any time, and she demanded that the ladies she designed for come to her, often, for fittings. She did not care about the desires or requests of the women she dressed, and was notorious for ignoring such trifles. The characteristically careful and measured restraint of her designs could not be applied to her personal interactions with her clientele. Essentially she would tell people to shut up and trust her.

In response to any confusion over such a stance, Valentina would archly reply that if she was trusted to make a piece for someone, then that person should understand that the designer knew better than the client how to make it. Her attitude did not interfere with her success. Valentina never wanted for work through thirty years in business. Though prohibitively expensive to most (about $600 for a single dress in the early 1950s, though she really preferred to design entire wardrobes, and usually did) her work was so iconic, so influential, that in the 1940s it became common to refer to a simple, unadorned dress as “a poor man’s Valentina”.

The designer herself was, from the beginning of her fashion career, often her own model; professionally and when simply wearing her own designs out in the world. Supposedly, back in Russia, she had been a model, a background familiar to many of the starlets she dressed. As difficult as she could be, her clients were devoted to her, to her brand, and many became personal friends. Her closest famous friend, likely lover, and the star over which Valentina held the most influence was the lovely and reclusive Greta Garbo.

Valentina and Garbo were, at one point, so close that Garbo moved into Valentina’s apartment building, specifically so that the two ladies could be in each others proximity. Valentina instructed Garbo on what to read, what media she should consume, and literally created her iconic personal style. They were physically similar in appearance, and supposedly, when the pair was out together in public, the designer and actress were often confused for each other.

There are many stories about Valentina signing Garbo’s autograph when adoring fans approached under the assumption that the designer was the movie-star (Valentina was known to have called herself “the gothic version” of Garbo). Garbo wore Valentina’s creations in films, on red carpets, and even in her personal life; she became a walking advertisement for Valentina’s brand.

Besides their looks, there were many parallels between the lives of Valentina and Garbo. The problems began when Valentina’s husband Schlee, who was her business manager, became Garbo’s ‘advisor’. Depending on what you read, details of this story differ. What does seem to be consistent is that the three of them were, at least for a time, romantically entwined, until Schlee left his wife for Garbo. At some point Garbo began to spurn his affections (possibly because of other affairs). Though it does not appear that they ever divorced, when Valentina retired and closed her brand in 1957, it likely influenced by the end of her marriage.

It is impossible to know how Valentina would have fared as a designer in the 60s and 70s, her work was very much for the adult woman (though never matronly), and the future of fashion in the mid twentieth century shifted notably towards a more youthful look. She left fashion at a high point in her career, and though this may not have been purposeful, it did save her from having to rework her design ethic to stay relevant in the coming decades.

In 1964, George Schlee died of a heart attack while on a trip to Paris with Garbo. Garbo did not attend his funeral, and for whatever reason, that was the point at which the friendship between the two women became unsalvageable. However, neither woman moved out of their shared apartment building, they remained neighbors long after Schlee died. Not just a matter of being on good terms, they reportedly HATED each other. Through intermediaries, a plan and strict schedule were worked out, for when each would leave or return to their apartments. Both women adhered to this religiously, to ensure they never again had to so much as see each other or, god forbid, interact.

After a long battle with Parkinson’s disease, Valentina died in New York City in 1989, around 90 years old. Very few extant pieces of clothing designed by Valentia remain, even fewer are available to purchase. Because of her aesthetic, the timeless nature of her designs, and because of the quality of her craftsmanship, much of the clothing Valentina made was literally worn to death. These pieces were purchased for huge sums of money, and then worn for years until they fell apart. There are museums and archives around the world that do have Valentina Gowns (and her other design work) as part of their permanent collections, including the Fashion and Textile Museum (at FIT) and the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Pingback: 15 Fashion Exhibits You Can’t Miss in 2020 – The Vintage Woman

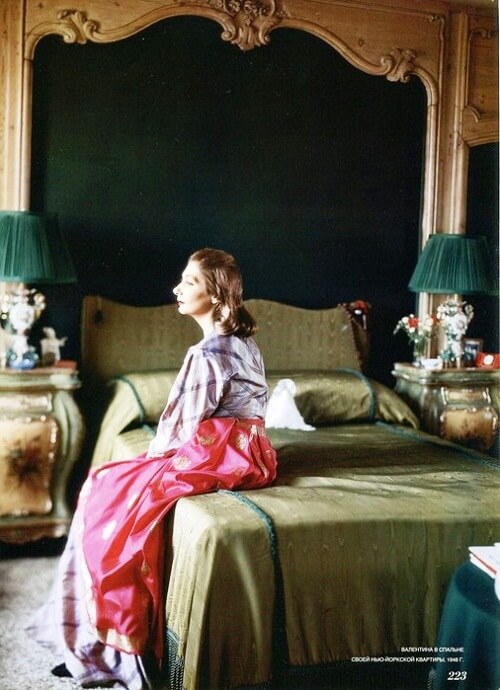

Fascinating to see her sitting on her bed. She showed me round the apartment in 1984 and told me that the frame behind the bed was half a picture frame. It could be so. I think she was born way before 1899. More likely 1889. Hard to tell. She was certainly full of mystery.