The Life Of A Chorus Girl

It’s 1929 on the homestead and you’re bored senseless every day. At 18, there seems more to life in the dozens of Hollywood magazines strewn across your floor than your own everyday occurrences. You’re not interested in marrying Georgie down the street and wish your parents would stop trying to hint about it. The cows, cooking, and babysitting are doing nothing to quell the brewing verve for life. You reach an unprecedented point of frustration and resolve to storm into New York in search of independence and the limelight.

For a young woman wishing to make a career on stage in the 1920s and ’30s, her easiest place of entry would’ve been the chorus line (as evidenced by the Wikipedia pages of stars like Paulette Goddard, Barbara Stanwyck, Billie Dove, and so many more). So, what would have been in store for the aspiring starlet who gets her start as a chorus girl?

As it turns out, a mixed bag of competition, camaraderie, physical toil, penny-pinching, tight schedules, new sights, and life experience unimaginable to previous generations.

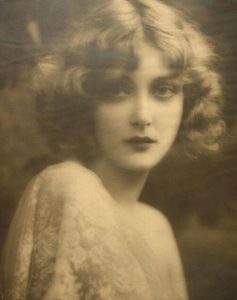

Let’s start with what led the average American girl to try her luck on the stage. Well into the 1920s, the chorus girl was mythologized in newspapers, film, and tabloids as a sort of Cinderella-like figure. Stories of chorus girls who captured the hearts of wealthy society men promulgated front-page news. Headlines such as, “Danced Barefoot Into His Heart: Chorus Girl’s Pink Tootsie-Wootsies Won Bibbins, a Princeton Student” seemed to many like real-world fairy tales. The success stories of Lilian Russel and Billie Dove (both rose from the chorus and married into wealth) emboldened the narrative that with a little pluck and the poise of a dancer, any girl had a chance of marrying their prince charming–polite, suave, and all too willing to share his castle with you.

By today’s standards, this idea seems the antithesis of independence and happiness. Although women were certainly taking up jobs during the ’20s and ’30s, it was still generally expected that they would give the majority of their lives to marriage and motherhood. Once a woman dedicated her life to her family, the quality of her life and that of her children rested on her husband’s financial success. For the early 20th century woman, selecting a good husband was taken as seriously as we take selecting our careers.

Added to that, a chorus girl didn’t need to sweat and clean as much as Cinderella. Descriptions of life as a chorus girl painted a picture of leisure, opportunity, and adventure. Writers of chorus girl life, most prominently, Roy. L. McCardell describes the career as rehearsing for four hours and performing at night with the in-between hours filled with “gossiping, eating candy, doing fancy work, or just taking it easy”, in addition to regularly receiving hats, dresses, and dinners from male admirers.

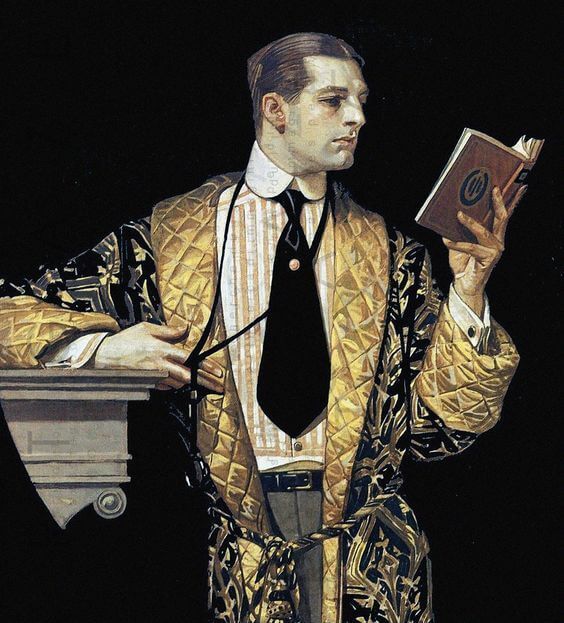

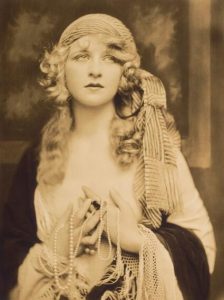

The profession not only seemed opportunistically fertile but it was also bolstered with the general pursuit of beauty most women shared. The highly popular series of productions, Ziegfeld Follies were known for their lavish sets and costumes as much as they were for their beautiful female performers. Collectively called “Ziegfeld Girls”, a great many were chorus line dancers. Florence Ziegfeld Jr., an impresario of the shows, was known to have an eye for spotting exceptionally beautiful women for his stage. By 1914, newspapers and magazines were churning out articles with headlines like, “How I pick my Beauties” or “Picking out pretty girls for the stage.” Numerous beauty advice articles pitched their advice on makeup, hair, and figure keeping, under the general message of “You too can be a Ziegfeld Girl!”

The combination of the stories of chorus girls and the stunningly beautiful Ziegfeld girls danced well together. It resulted in a successful marketing campaign whether it was intentional or not. Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, girls auditioned to be chorus dancers in droves and competition reached its peak in the 1930s. Comparatively, we can look at our own modern appeals to being a “content creator”, “working from home while pursuing your passion”, to get the sense that they held similar hopes of receiving improved working conditions. After all, if it’s just 4 hours of dancing and then paling around, that would surely beat the full-time job of helping your mother with the cooking and cleaning! Even if you had to travel to an unfamiliar city, compete with other girls, and drain your wallet in the process, there was a wider pool of suitors guaranteed to come from wealthy backgrounds (or so the papers said). The dread of marrying Georgie down the street would disappear and in its place: new sights, parties, dresses, hats, and a host of suitors that would have previously been out of range.

That being said, not all aspiring chorus dancers fled to auditions to land a wealthy beau. In And She Danced for A King – Memoirs of a Rockette, Margaret “Peggy” Morrison pursued the profession due to travel lust and a love for dance. Peggy’s letters home are an invaluable record of the lifestyle of a chorus girl.

Peggy’s dance journey began in 1927 when her parents presented the 16-year-old girl with 2 choices, “either nice clothes like your sister had her senior year or dance lessons, but you can’t have both.” By choosing dance lessons, Peggy not only secured a career but a career that comes with nice clothes. A wise decision, indeed. The next few years of Peggy’s adolescence were dedicated to ballet and tap lessons.

In 1931, Peggy left her hometown in Ohio to take her dance shoes to New York City stages. Peggy’s letters describe a rough start in showbiz made worse by The Depression and the unstable payment conditions of theatrical performers. In an unfamiliar city with just fifty dollars to her name, she became expertly frugal. Between waiting tables and attending auditions, she survived off of a dollar a day thanks to Automat sandwiches and salads. Automats were essentially vending machines filled with packaged meals for the cost of a coin. They remained a mainstay in New York City until the 1970s. A comparable experience might be if you were to survive solely off of the cheapest options in your college cafeteria (those $4 sandwiches and salads sitting in chillers on the side).

Peggy danced her first steps in the New York City theatre world when she got accepted into the chorus line of Three’s a Crowd. Her letters during this time describe rehearsing morning, afternoon, evening, and night – a far cry from the four hours of rehearsal with the rest to “take it easy”, reported by chorus life columnists. When it came to rehearsals at night, Peggy writes, “Jerry, our stage mgr., said we may be working even as late as 1 or 2 am!”

Essential for the challenges of chorus girl life was camaraderie. Long rehearsal hours with no sign of pay until opening night meant having to sustain one paycheck for about 2-3 months. In one of her letters, Peggy brags that she, “never managed so skimpingly in all my life!” Despite her positive attitude, having to eat minimally while dancing morning, afternoon, evening, and night would make anyone miserable. There were much better chances of withstanding the workload of a chorus girl if you at least had a friend who understood the same problems.

Peggy felt lucky to have her roommate, Kathyrn, performing in the same show. Even luckier was that she had Kathyrn to walk home with within the dark morning hours after rehearsals. Though not many instances of sexual harassment were recorded in those days, you can bet that if it’s a problem today it was probably a worse problem in 1931.

Chorus girls were shamelessly sexualized in film and stage productions. The 1934 pre-code comedy Hips Hips Hooray (among others) portrays a group of chorus girls in outfits roughly equivalent to what you could find at Burning Man today (backless halter tops opened in the front that covered the essentials paired with short shorts and long stockings.) The giggly chorus girls are available to two salesmen who are in need of kisses to test out their line of new flavoured lipsticks. “Come ‘ere, toots” and the girls are all too happy to kiss the fellas, no questions asked.

While exiting one of the shows for Three’s a Crowd, Peggy writes of how she had to fight her way out of the stage door due to being crowded by a flock of men. She writes, “Those Yale boys are kind of hard to convince that you don’t care for their company. Boys! What we didn’t say to some of them when they’d tag us! It’s a marvelous experience in how to take care of yourself!”

A contradictory idea of chorus girls as “a type of sexually liberated girl” who could also settle down in marriage when duty called filled the imaginations of writers, and consequently, the public. Columnists emphasized the sexual desirability of chorus girls in sensationalist headlines such as, “Showgirl Miss Virginia Lee Engaged to Eleven Men.” The very modern, daring, and somewhat scandalous lifestyles of showgirls were a hot topic in literature as well. Books, such as Madge Merton’s “Confessions of a Chorus Girl”, Grace White’s “Fallen by the Wayside, or a Chorus Girl’s Luck”, Frank Deshan’s “Chorus Girls I have Known” were eaten up by the public. The portrayal of the chorus girl in books and articles was generally that of a respectable young woman enjoying a modern lifestyle of independence. She dates college boys, travels, attends late-night parties, but in the end, remains a “‘good girl”.

While there are certainly mentions of dates and parties in Peggy’s memoir, the vast majority of her letters are more concerned with simply keeping up her physical strength and financial reserves. She writes often of the physical toil of rehearsals. Just in her first show, she describes being “so sore I can hardly walk or bend”, and of how fortunate she felt when she and Kathyrn were “almost all over our stiffness, and we can even walk downstairs and sit down…”

On several occasions during the tour of Three’s a Crowd, the salaries of the chorus girls were cut by $10 due to poor audience turnout. The Great Depression created a domino effect that shook up the financial stability of theatre revues. If the revue couldn’t accrue enough from tickets, they simply had to prioritize travel expenses, costumes, sets, and paying theatre stars their worth in gold.

Peggy sums up her feelings on paycheck cuts in one letter, “We go back to our cut salary-40 bucks. Isn’t that the limit? […] Collegians [the orchestra] have taken about a 45% cut, and the 3 stars will play for expenses only. So you see they’re doing everything in their power to keep going. It burns us up -the cut again- but what can one do… But there’s just nothing to do but take it. It’s better than nothing…”

In fact, the bulk of Peggy’s letters concern financial difficulties. In an effort to compensate for the cut paychecks, Peggy and Kathryn would try to do without, whenever they could. They skipped meals, frequented secondhand shops, and purchased show tickets for one family member at a time. Despite keeping a vigilant eye on her finances, there were times when Peggy had to ask for financial assistance. Written in her every request was an embarrassed “I hate to think of asking you to send me money….” During The Great Depression, it was common practice for every member of the family to do their part to keep the family financially afloat. The sense of guilt at having to ask for money, rather than provide it, must have been embarrassing, indeed. In her letters, Peggy was very adamant about paying back any financial assistance she received from her family.

Stretching her paycheck for months at a time while paying rent, agent fees, and sending home some portion of money, sometimes landed Peggy in financial straits. Written while she was touring for Three’s a Crowd, Peggy describes what she had to work with:

“You say you are glad I’m eating enough. Well, it is a necessary evil and I’ve tried so hard to manage on what I brought. But the news is sad. I have another rent of $8 to pay and live besides. I just counted my money and I have exactly $16.28 left. That’s not so hot. It takes about $1.25 to 1.40 or .50 a day for me to live on now during rehearsals. Isn’t that terrible? We try to do less and it can’t be done…. “

Peggy’s fortunes changed for the better when she joined the Paramount chorus line. The glamorous perks of show business were finally beginning to show themselves albeit for the price of increased physical toil and tighter schedules. Paramount had been set to take their shows to Paris and Peggy was all too thrilled to travel. When she arrived in Le Havre, France, Peggy was “thrilled to pieces” and described a sunset along a ‘beautiful green shore” as well as gorgeous lights twinkling in the dark of night. Her time in France was punctuated with French language classes, limousines, ritzy hotels where “all the biggest shots in the Paramount organization” stayed, and parties with other Americans in France. Peggy excelled at French and forged friendships with the natives. One of whom was Rennee, the son of a millionaire champagne maker. Their brand, Heidsieck, is still thriving today.

Although she took a pay cut by joining Paramount (from $50 a week to $27.50 a week), the company provided her with more benefits. Paramount paid for travel expenses, food, and even her French language classes at a college in France. Perhaps one of the best perks of joining Paramount was being able to eat on more than a dollar a day. Enthused, she wrote home about a five-course meal consisting of wine, soup, fish, potatoes, steak, asparagus, cheese and crackers, salad, dessert, and coffee which she made sure to point out was “strong and thick”. It was common during The Great Depression to dilute coffee to increase its longevity. Amazed, she comments, “It takes about an hour to go through all the courses. Oh yes, fruit comes after the cheese. It’s a positive scream.”

On the topic of “positive screams”, remember when 16-year-old Peggy was given the option of “nice clothes” or “dance lessons”? Paramount took their show to Paris’s Folies Bergere music hall where Peggy modelled a green evening gown. She wrote, “All the kids say it’s the most stunning of all the ones shown. It’s pale green. My hair is so very blonde that it just looks great. I’ve never been so thrilled with anything in my life.” She describes other costumes under Paramount to be “the best of velvets, furs, silks, and satins.” It looks like she was able to get both sides of the deal after all!

When it came to the backstage life of the Paramount shows, the workload was so overwhelmingly exhausting that she found herself reaching her limit. Rehearsals until 2 am with the expectation of being dressed and in makeup by 6:30 am just about burned through Peggy’s positive attitude. The rehearsals were “awful long and hard -about 14 choruses in all! […] I ask you! I’m simply dead…” To make matters worse, they worked under Mickey Rasset who had a reputation for showering his performers in praise when they did well and psychologically abusing them when they did not meet his standards.

In a lengthy rant, she wrote that Rasset has “rehearsed us until we were all hysterical and crying- even for the shows on stage. It’s a perfect fright. He [Rasset] doesn’t think he can get anything out of us unless he calls us ‘bitches, bastards, god-damned idiots’, etc!” She described her own experience of it as being worked “as if you are some sort of machine and instead of filling you up with gas and oil to make you work, you are filled with swear words, threats, etc.!”

An unfortunate reality of working in a chorus line is that you practically had to live with 20-30 girls while on tour. Social relations within the group could make or break your chances of staying with a company or not. Once they began performing in Paris’s famed Follies Bergere music hall, Peggy caught the eye of Mistinguett, a huge celebrity and star of the Follies. Peggy recalled how the attention she received from the star often gave her “the willies” and feared that Mistinguett was harbouring an agenda. Nevertheless, attracted by her kindness, humour, zest, and overall colourful personality, Peggy accepted preferential treatment from Mistinguett for some time.

Thanks to her new benefactor, Peggy was given different (often better) costumes than the other chorus dancers. She was regularly invited to Mistinguett’s dressing room where she was welcomed to use her radio and eat bonbon. Mistinguett also provided emotional support for when Peggy was run down from rehearsals and in tears from the pressures of show businesses.

Yet, in the end, Peggy remained suspicious. Her suspicions were confirmed when one day Mistinguett called her into her dressing room and offered her stardom, as she had done for Maurice Chevalier. Peggy’s feathers were ruffled at having been given preferential treatment so that she can be profited off of. She writes, “ I prefer marriage to stardom…she’s powerful and wealthy and famous and all that, and she can do everything she wants, but if she ‘wants’ me I’m afraid she’ll get stung this once, no matter what her pay is.”

Peggy’s involvement with Mistinguett also cost her her reputation within the group of chorus dancers. She received ridicule, shunning, and a social environment that grew progressively hostile. She wrote to her mother that “They’ve been at me and at me, every blasted one of them…” Unable to stand the discomforting social environment wrought by the other chorus girls and Mistinguett, Peggy booked a trip home.

In the States, she continued her career with The American Folies Bergere and later The Rockettes. Throughout her extensive dancing career, she performed in numerous exotic locations such as Brazil, France again, Argentina, and Canada. Her memoirs have illuminated the struggles, joys, mistreatment, and glamour of the life of a chorus girl. Working as a dancer in a chorus line, like most professions, involves advantages that may or may not be too weighed down by disadvantages. In the end, it’s a personal journey of learning your worth and limitations. Next time you read that your favourite old Hollywood star started out as a chorus dancer, think of all the pluck, poise, and grit that was necessary to navigate the terrain of musical show businesses.