A History Of Feedsack Clothing

Fashion trends are often influenced by political and socioeconomic factors. Due to the pandemic, our shopping options are limited and we have more free time at home. If you’re anything like me, you’ve taken this time to work on sewing projects that have piled up. Maybe you have picked up sewing as a hobby for the first time, making dresses from vintage patterns with found fabrics. Or perhaps you’ve repurposed quilt tops or redesigned wool blankets into coats. This is not so different to a time when the stock market crashed, or when wartime rationing dictated consumer decisions. Cotton commodity bags, better known to us as “feedsacks” were repurposed for just about everything.

In the 1800s, rural folks would repurpose things out of necessity. Farmers bought items in bulk, and their names were sometimes stamped to canvas, osnaburg, or muslin sacks AKA “chicken linen”. Sacks were brought back to use again, comparable to reusable grocery bags of today. Some places would even pay a couple of cents if you returned the bags to the store. Eventually, millers found it easier to pre-fill the bags.

In 1846, Elias Howe patented the lockstitch sewing machine. The technology of this invention ensured secure, tight stitching which created a reliable seam for containing grains, meals, and powders. Paired with strong, tightly-woven, and newly inexpensive cotton percale, even the finest powdered contents could not sieve through. By the mid-1850s cotton or linen bags replaced tin containers, and heavy wooden boxes and barrels.

Repurposing increased in popularity during WWI, and by 1925 roughly 42 mills made fabric bags. Manufacturers began to recognize a lucrative opportunity in marketing these bags to women. Mills began employing their own fabric designers. Test markets for fabric prints emerged and the popular ones were produced for fabric stores. Brands gained loyalty as women started to recognize which companies they loved and trusted. There was a transfer of buying power from the man to the woman and was a way for women to contribute to the financial stability of the household. When money was scarce during the Great Depression, some women claimed their kids would have been running around naked had it not been for feedsacks.

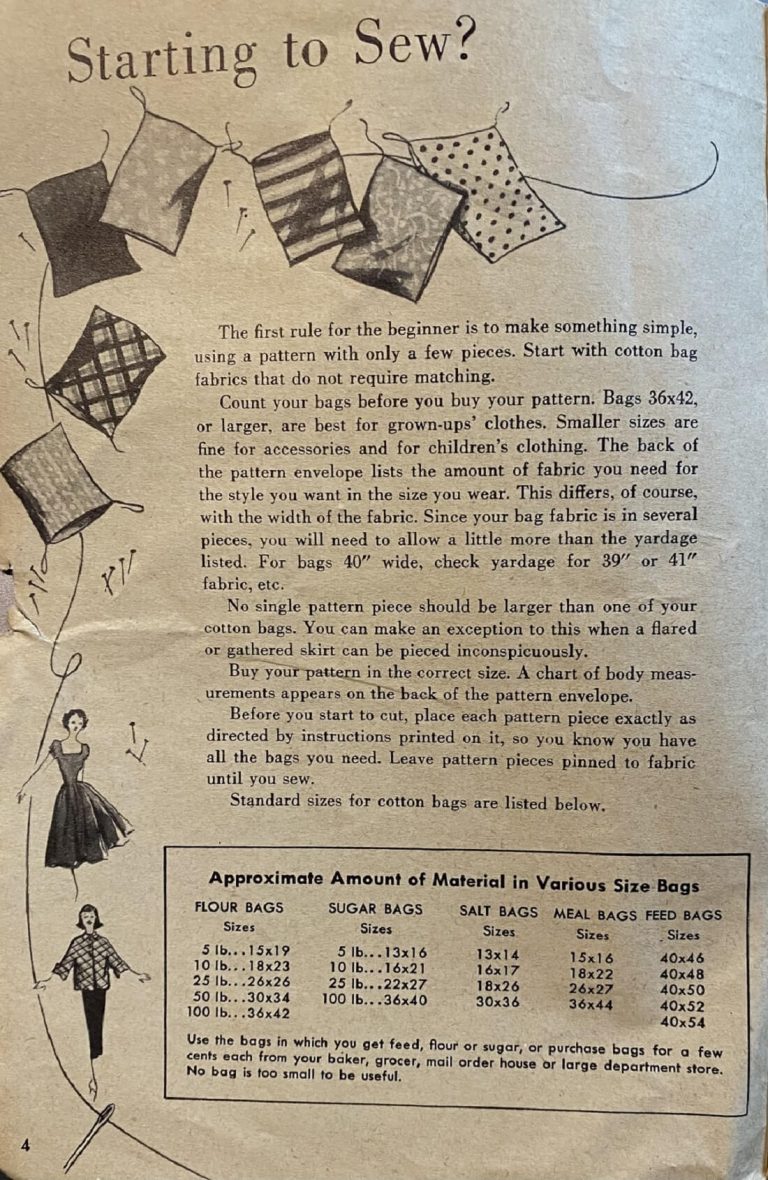

100lb. flour sacks were approximately 36×42” in size, roughly 1×1.5 yards. To make a dress that required three yards of fabric, a woman could pay 40-60¢ at Sears & Roebuck or alternatively collect two or three flour bags. For the sewing projects requiring more than one bag, you could go buy another full feed bag with the same print on it or hunt for the same fabric elsewhere. Some ladies hosted bag parties or traded with friends at home demonstration clubs. Clothing items requiring less fabric were trendy, creating shorter hemlines for skirts and dresses. Fabric options included plain colours, border prints, plaids, stripes, and even patriotic propaganda cartoons during wartime. Eventually came popular culture motifs such as Gone with the Wind, and licensed Disney character prints. There were also embroidery templates and patterns for dolls, sometimes the only toy a child would have.

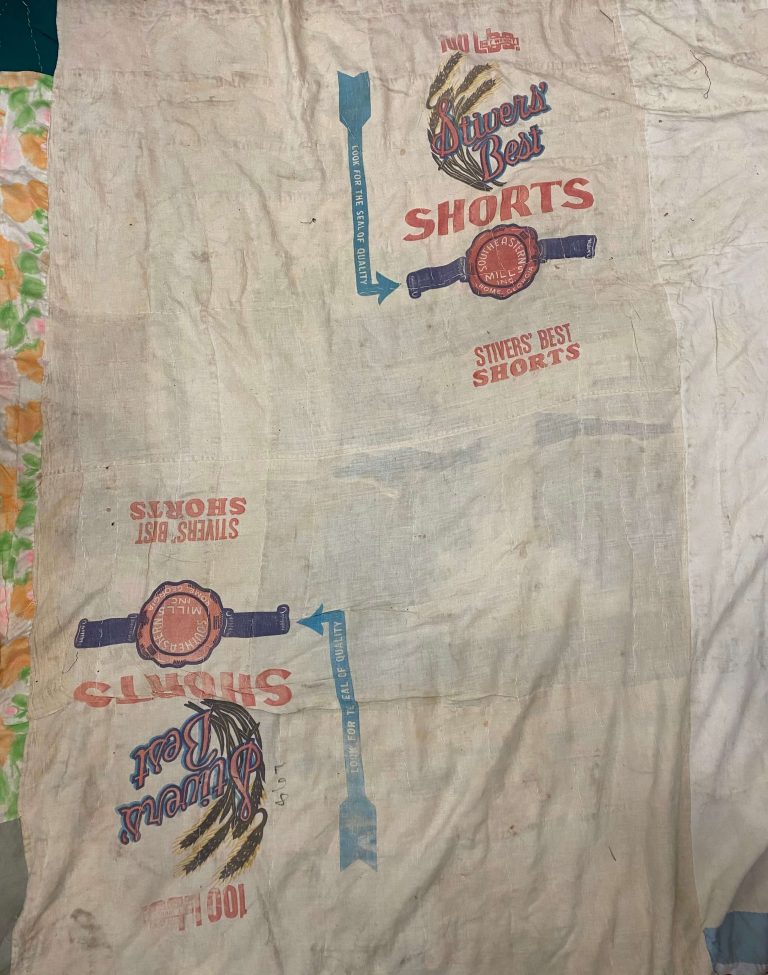

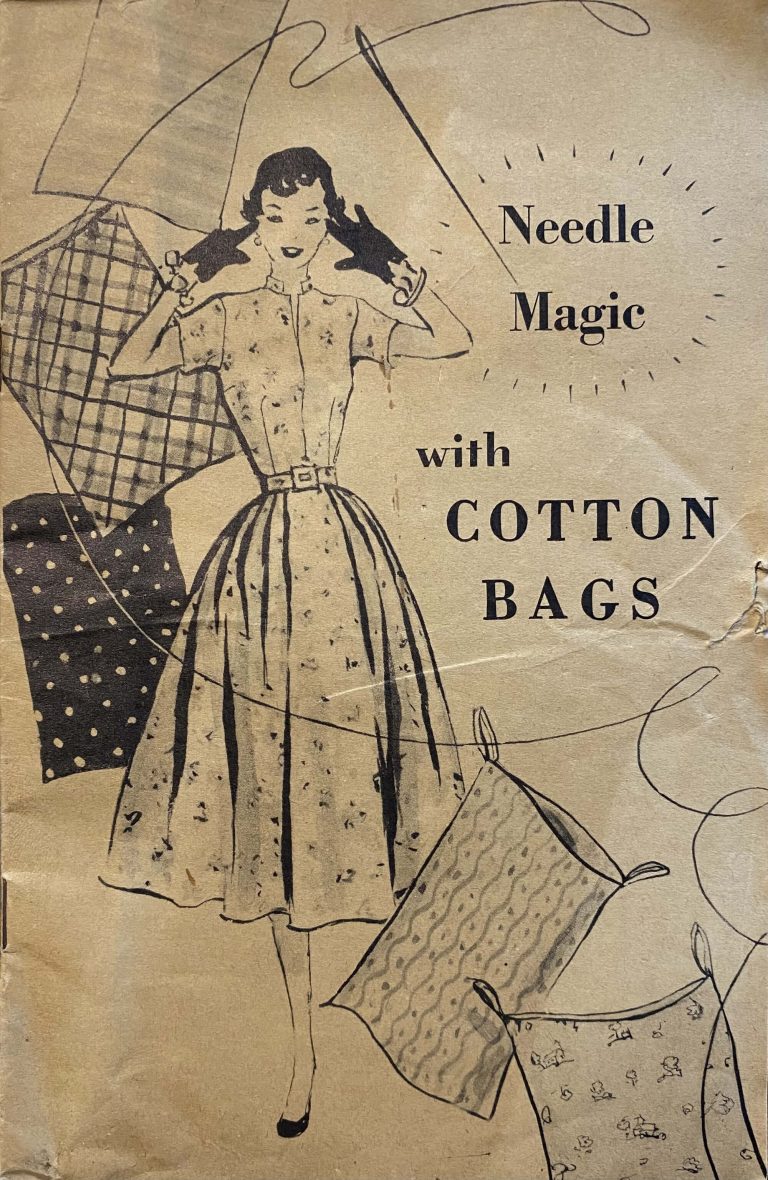

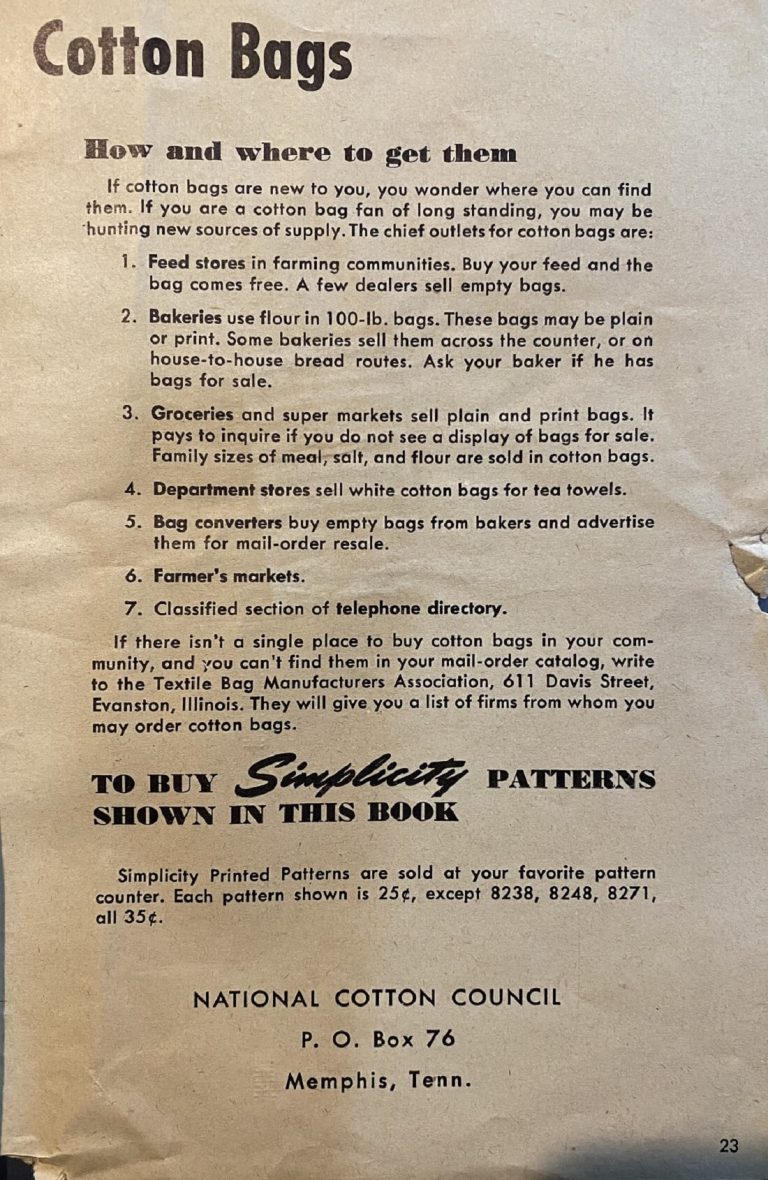

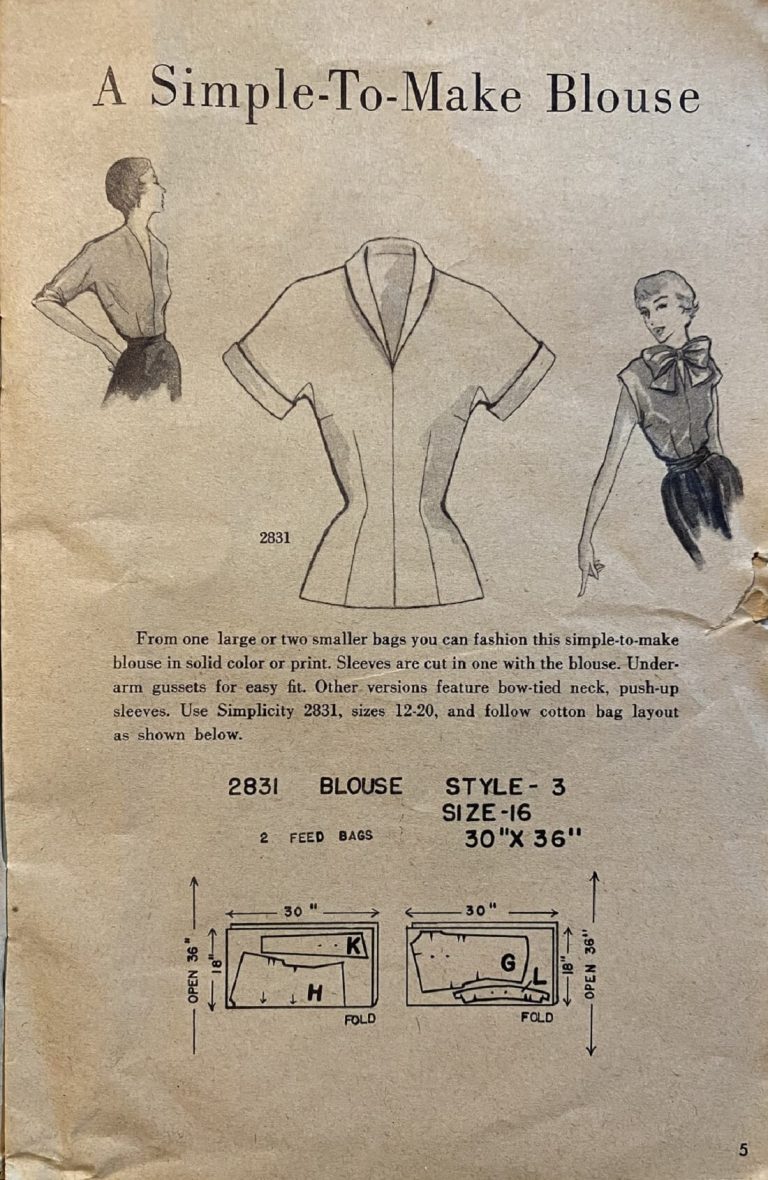

Fabric could be prepared for use firstly by removing the water-soluble ink, then starching and pressing. The result was a relatively comparable alternative to store-bought bolt fabric. Knowing that the ink-stamped labels and washing instructions were arduous to remove, companies switched to easier to remove paper labels. Some mills had labels sewn right into the seam, as well as instructions for string removal. How-to pamphlets were circulated with patterns and creative ideas.

During WWII, the military required certain fabrics. Urban and suburban women were encouraged to reuse feedsacks in addition to rural women. What was once seen by some as a symbol of poverty was newly boasted as patriotic. The Textile Bag Manufacturers Association slogan was “a yard saved was a yard gained for victory.” Using every last bit of fabric was important. Tiny scraps were used as repair patches or found their way into intricate quilts. The thick, twine-like side seam threads were even crocheted into doilies. As a society, if we had continued to use every last bit of everything like this, and adopted less of a consumer mindset, then maybe we would have had a less negative impact on the environment.

Cloth bags were less common by the late 1940s as plastic and paper bags were more sanitary and cheaper to produce. There was some attempt to slow the momentum of this changeover, though. The National Cotton Council had design contests to be crowned the “National Cotton Bag Sewing Queen.” Fashion shows and exhibitions with creative submissions kept the spirit of fashionable repurposing alive. Continued advertisements countered rural stereotypes, as glamorous types didn’t love the idea of wearing something that held fertilizer. But all good things must come to an end, and by the 1960s feedsacks were mostly phased out.

Verifying the authenticity of feedsacks can be done in a few ways. The easiest way is finding an actual in-tact feedsack, with or without a label. If not in-tact, look for holes, as the thick lock-stitched threads tend to leave quite large holes behind. Sometimes you can find the holes on finished garments, be sure to check for hidden ones in the seam allowances. You can also compare fabric feel and visual texture to see if it resembles fabric that is known to be feedsack. Feedsack has a nice feel- not scratchy or overly thick. Worn and loved feedsack items are soft as can be, so comfortable to wear. Feedsack items are one of my favourite things to collect because of the hundreds of thousands of prints created. It’s extremely exciting, as I never know what I’ll find. Unlike women of the past, who found for their third or fourth matching bag, I’m not likely to find the same fabric twice.